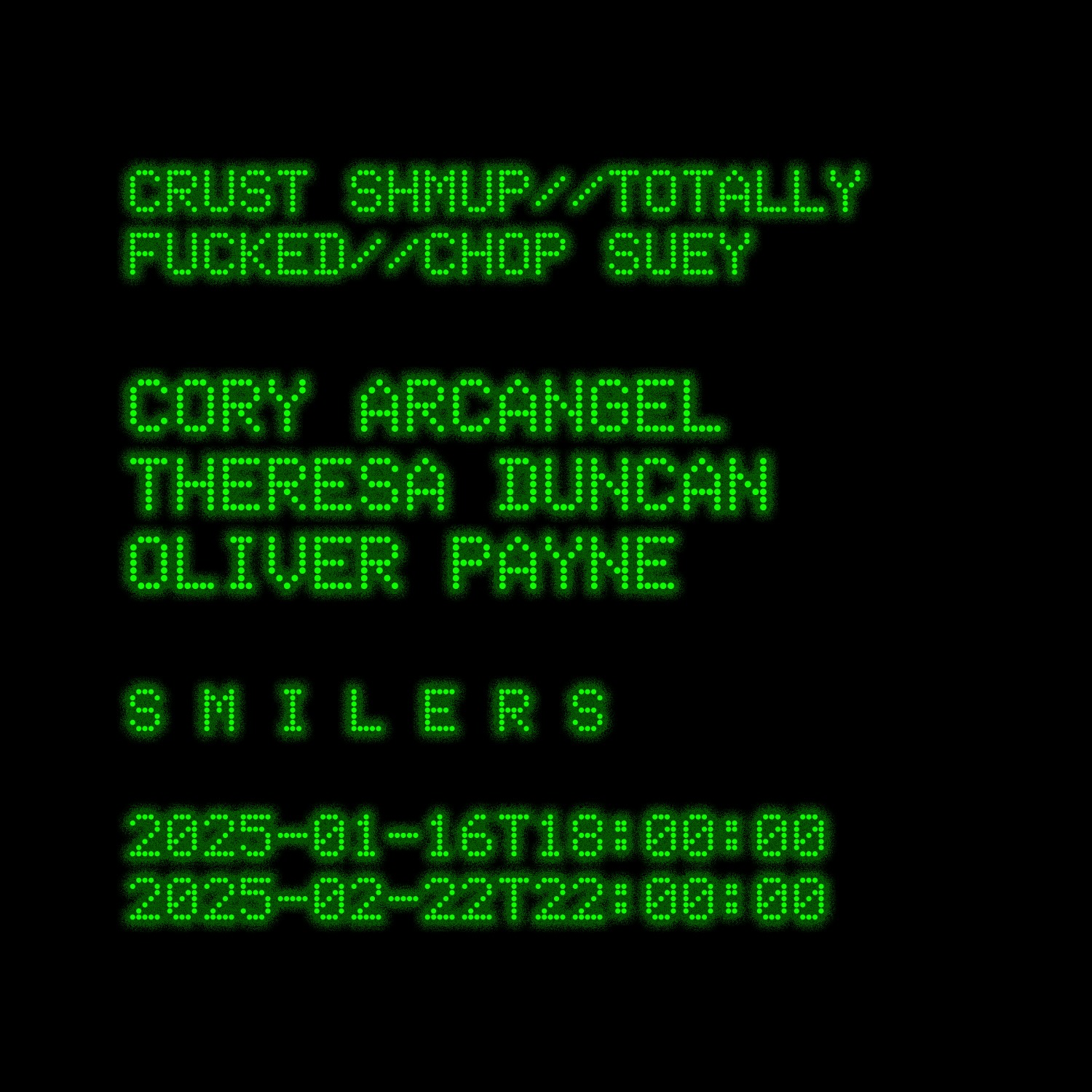

CRUST SHMUP//TOTALLY

FUCKED//CHOP SUEY

Cory Arcangel

Theresa Duncan

Oliver Payne

January 16—February 22, 2025

S M I L E R S’ inaugural exhibition is a celebration of gaming and nascent creativity, featuring three artists who are kindred in their unconventional paths toward artistic recognition. Cory Arcangel, Theresa Duncan, and Oliver Payne engage videogames as a form of expression with very different outcomes; however, they are united through a mutual arrival to this medium through freeform immersion in music, technology, and various subcultures. As a trio, Payne’s CRUST SHMUP (2024), Arcangel’s Totally Fucked (2003), and Duncan’s Chop Suey (1995, co-created with Monica Gesue) articulate common ground between the works’ multitalented creators, rather than suggest any stylistic relationships. Graphic and structural differences between videogame genres are instead foregrounded by the works’ positioning in zones of casual, familiar settings. Also linking these artists is the collaborative spirit of their early careers, echoing the connective virtue of gaming and its incomparable reach as both an art form and developmental touchstone of the digital age.

🍄

Cory Arcangel (born 1978) is an artist, composer, and digital archivist. He is singularly influential amongst a generation of creators who came of age in tandem with the internet and home computing. Arcangel studied classical guitar at Oberlin Conservatory of Music before refocusing on avant-garde composition and music technology. This intersection with electronic music led to the collaborative release with Paul B. Davis, Joseph Beuckman, and Joe Bonn, of the self-titled record The 8-bit Construction Set (2001), a chiptune DJ battle and concept album in which one side was composed on an Atari 800 and the other on a Commodore 64. Arcangel’s key exploration of outdated home entertainment systems and computers has given him a unique duality as both pioneer and savior of software-based art—a medium which by nature exists on the verge of obsolescence. From 2011 (the same year as his history-making solo exhibition, Pro Tools, at the Whitney) to 2014, Arcangel spearheaded the extraction and archiving of Andy Warhol’s digital drawings made in 1985 with the Amiga 1000, long thought to be lost. He is a frequent collaborator with Rhizome, an organization that both maintains a platform for and preserves digital-born art [the same organization that in 2015 led a conservation effort to make The Theresa Duncan CD-ROMs free to play on any web browser]. In Arcangel’s most recent cooperation with Rhizome (and the Michel Majerus Estate), he mined the contents of Majerus’ Apple PowerBook G3 (manufactured between 1997 and 2001) to reveal insights into the artist’s previously unexplored late career digital studio. Often sharing his technological literacy to expand upon the lineage of new and experimental media (and to occasionally poke fun at proprietary software tools), the ethos of open-source is strong in Arcangel’s approach to art.

Totally Fucked is among the earliest examples of Arcangel’s iconic modifications of classic videogames, made while the artist was just twenty-five years old and operating from underneath his lofted bed. Super Mario (of the 1985 release for Nintendo Entertainment System) stands in an infinite loop on top of an item block, unable to move but gesturing left and right—the only two directions the character’s (and maybe our) restrictive world allows. The scenery of the Super Mario Bros. universe has been scrubbed, leaving a blue void. Arcangel resists sentimentality with his hack and instead makes an unprecedented artistic interruption of a beloved gaming narrative. His intervention is profound in its simplicity, if not soft nihilism. We’re all stuck, but perhaps a masterstroke of playful humor can set us free.

💿

Theresa Duncan (1966–2007) was a videogame designer, filmmaker, and savvy cyberspace native through her authorship of an esteemed blog titled The Wit of the Staircase. Duncan’s informal artistic background is befitting of her imaginative contributions to gaming that were completely unhindered by convention. Chop Suey is the first of a trilogy of “girl games” released as CD-ROMs that also includes Smarty (1996) and Zero Zero (1997), all three groundbreaking as a reaction to prevailing male themes and market forces in the videogame industry. Duncan met her main collaborator on Chop Suey, Monica Gesue, while working at the World Bank in Washington, DC. Duncan was a fixture amongst cross-pollinating musical and artistic circles, meeting several additional Chop Suey contributors from within the city’s endlessly influential punk and hardcore scenes. Notably, Brendan Canty (Fugazi, The Messthetics, Rites of Spring) scored the game’s music/sound, and Ian Svenonious (Nation of Ulysses, the Make-Up, Escape-ism) created the illustrations. Duncan also recruited David Sedaris as the game’s narrator after hearing his voice on NPR. The result of this alchemical meeting of minds and talents is tangibly magical and by this point legend, with Duncan as the bold heroine at the center. Despite neither Duncan nor Gesue having prior experience in making a game, the software development company where the pair had found work greenlit their project. As told by Gesue, this was largely due to Duncan’s magnetism and confidence in her purpose. Duncan’s can-do attitude expanded into filmmaking, and she continued to showcase her friends’ and collaborators’ gifts through her projects, including in The History of Glamour (1998). A semi-autobiographical commentary on fame, the animated short film was featured in the Whitney Biennial in 2000. Barely over the age of thirty, Duncan received widespread critical acclaim as both a filmmaker and game designer; of the latter, she remains among the very few who prioritized young girls as an audience.

Chop Suey is a point-and-click adventure that invites the player to create their own narrative experience. There are no preset objectives beyond exploration of the game’s brilliantly colorful midwestern cityscape, viewed from above like a map. Described as a “moving storybook”, the game’s zany characters, living scenery, and open-ended encounters verge on the surreal and serve to nurture emergent curiosities and creativity. Duncan and her collaborators achieved their own deeply original visual language with folk art in mind. Lighthearted and droll, the less written about this treasure of a game, the better—it should simply be played.

🕹️

Oliver Payne’s (born 1977) recent turn to videogames is rooted in his own personal and artistic legacy, defined by a deep appreciation for musical subgenres and participation in the fringes of British culture. Payne is also a longtime gamer. Payne garnered art world acknowledgment in the late 1990s through a set of short films he made with Nick Relph when they were both in their early twenties. The duo met at Kingston University in London where they were both repelled by its suburban conservatism; neither completed their degrees. Nonetheless, the art school experience served its purpose in introducing the two young men who came from similar backgrounds and recognized in each other a shared vibration. Both bucked against the trope of the “bad boy” upstart artist, and the immediate, polarizing attention Payne and his collaborator received seemed to miss the point entirely: that they were simply making films about what they knew, loved, or loathed. Driftwood (1999), House & Garage (2000), and Jungle (2001) (now considered a trilogy titled The Essential Selection and in the collection of Tate Modern) were created in raw, rapid succession, each going straight for the metaphorical jugular of British identity through onslaughts of rhythmic imagery that exposed societal hypocrisies and contradictions in a way that overly considered art cannot. Born at the height of the punk movement and immersed in graffiti, skateboard, and rave culture, Payne’s early work captures the emotion, irony, and irreverence of youthful rebellion with an authenticity that comes only from participation.

CRUST SHMUP is an anarcho, arcade, crust punk shoot-em-up inspired by Napalm Death’s debut album, SCUM (1987), as described by Payne. The creation of this game is somewhat of a story within a story, as a brief description of the band that started a musical genre—grindcore—in their teens is due. The “Napalm sound” (which is experienced in full force during gameplay) is a guttural vocal technique paired with distorted instruments played at high velocity and is yet another result of free, incipient experimentation with various musical tools and inspirations. Hard-edged and aggressive in appearance, CRUST SHMUP’s objective is, counterintuitively, to evade conflict to survive, as Napalm’s lyrics and politics were explicitly pacifist. Given his long-standing relationship with contradictory forces, Payne amplifies this intensity as both creator and superfan with a game that honors the influences that shaped him.

🍄 💿 🕹️

All three works on display upend the concept of winning as the goal of gameplay and do so in ways that reflect the sensibilities and unruliness of their authors. Totally Fucked is straight-up unplayable, with the original cartridge tweaked by the often satirical Arcangel in such a manner that precludes user interaction altogether. Chop Suey shirks notions of experience points, levels, and bosses—much like Duncan in endeavoring to design a complex computer game without the model credentials, an idea unfathomable to most. CRUST SHMUP, a shoot-em-up that rewards not shooting, may at face value seem humorously contrarian, but is in fact rooted in a powerful attraction to anarchic ideologies that Payne has both observed and been a part of. Formative interactions with music and technology, ranging from hardline to tangential, steered each of these artists toward their work with videogames. In S M I L E R S’ basement space—domestically outfitted to spark former selves to recall how they may have first encountered gaming—a fruitful player experience is the goal: videogames are the past, present, and future all at once.

Laura Tighe

January 16, 2025

CRUST SHMUP//TOTALLY FUCKED//CHOP SUEY was presented through the collaborative efforts of Laura Tighe and Mark Beasley.